Rabindranath Tagore is about ‘Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high…Where words come from the depth of truth’ etc. It is not Mr. Amir Khan alone who thinks this. So does, in fact, everyone else who has read him in any language. Well, these lines are something worthwhile for a person to be about. If one could put the essence of whole human existence in a few lines, Tagore has done that in this Gitanjali poem. There were instances of people harking back to these lines. Pakistani economist the late Mahbubul Haq quoted them in his Human Development Report, South Asia of 1997. Mr. Deva Gowda quoted it in Parliament when he was forced to resign as the Prime Minister of the country. And so on and so forth.

It is about a country that is yet to realize these words, be equal to them, let alone shaping itself after them. Does any country seem to be trying? It’s a six hundred fifty crore question, but the question needs to be asked, time and again perhaps. When Tagore sets up such a goal, clearly outlined, it’s your turn to decide whether you take up the challenge, and move towards it.

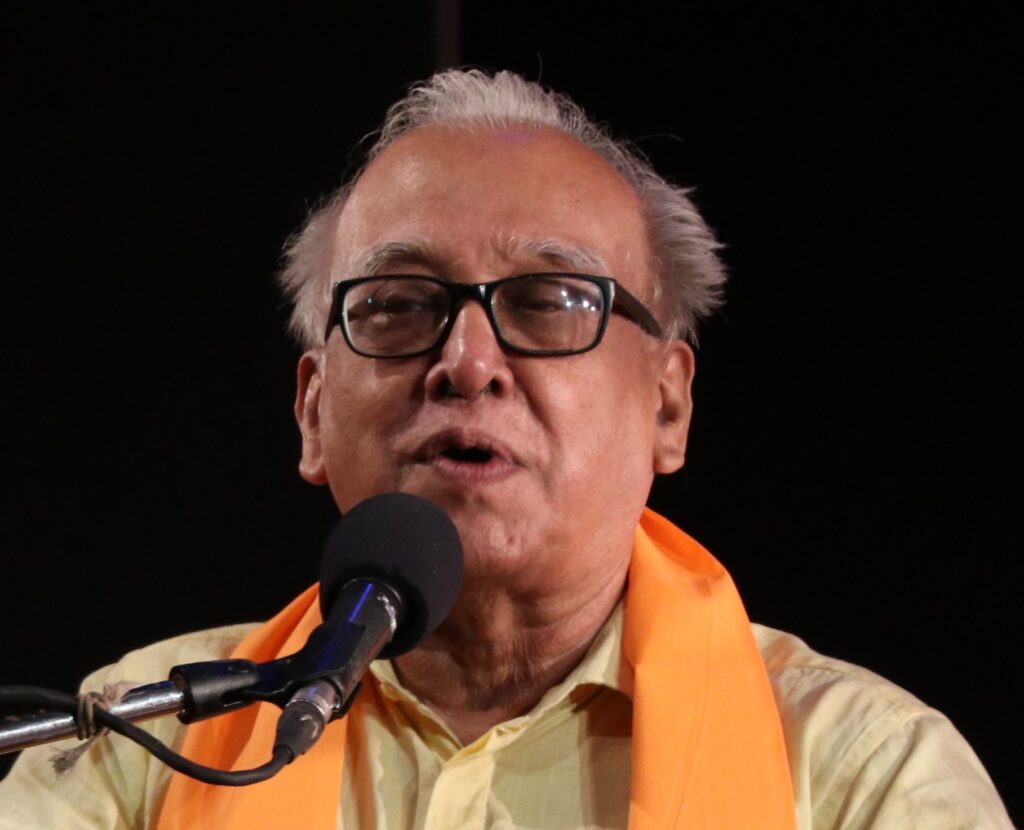

Yes, Tagore was a poet, a painter, a singer and composer of hundreds of songs, playwright and actor, a writer of fiction and myriad other things. Yet he concerned himself deeply with the human destiny of his country and, inevitably, with that of the world. He consistently asked the question—what is it that defines a human being? It is not a caste, creed, sex, language or a country, it’s just being born as a member of the human race. In his Chandalika, the ‘ untouchable’ girl, Prakriti, who, raising herself up from ignominy by the words of the Buddhist monk Ananda, spells out her own conviction—“Yes Ma,, that’s what he said : “You are the same as I am, human beings both. I’m thirsty, give me water. The water that quenches the thirst of a person is holy water, no less!” To Tagore, Hindus and Muslims, blacks and whites, and all human beings at that, share the same ‘holy’ brand of existence—humanity. None has to be shunned for any of the above accidental features that he or she may be born with.

What, again, defines a nation? Is it its geographical borders which politicians playfully keep on shifting about all the time? The India in which Tagore wrote is now trifurcated in three major countries. In the early days of our political struggle, Tagore didn’t like words becoming more important than human beings, than the suffering millions of the country in particular. The ideals of ‘Bharat Mata’ and ‘Bharat Lakshmi’, he said, were all wrong. The Bharat Mata wasn’t someone playing Veena on a peak of the Himalayas, she instead was the mother who lives in her hut in a decayed village and didn’t know what to feed her malaria-stricken child day after day. The Bharat Lakshmi was in no way a bark-clad damsel that watered plants in the hermitages of Vashishtha or Vishwamitra, she was rather the one who, famished or half-fed herself, cooked in a rich man’s house to put her son in an English school in order that he could become a ‘government clerk’ one day. For him, the ‘patriotism’ of doling out dreams was a delusion cooked up by the babu politicians. It was the toiling masses that have to be lifted out of their sufferings, whose liberation would mean the country’s true liberation. Not many people listened to him then, nor many do that even now. Bipin Chandra Pal, a fiery leader of pre-Gandhi Congress, branded Tagore’s patriotism wooly and unrealistic.

Nor was his patriotism was of the type– ‘My Country, Right or Wrong’, ‘It’s the Best Country in the World, the King/Queen of them all!’ He knew that such gloating might lead, and had often led, a country to imperialism. He condemned the plunder of Africa by the Western powers, as he almost cursed Japan for its aggression on China. He wrote back to the poet Yone Noguchi, who had sought Tagore’s support for Japan’s Asian designs, “I wish your people, whom I love, not victory, but remorse”.

Was he a mystic poet? Did he talk about a ‘God’ all the time? Well, he wasn’t and he didn’t. Tagore was the poet of humanity and of this world. As a poet of India he looked at it as the receptacle of ‘a great ocean of humanity’, composed of all—Aryans, non-Aryans, the Sakas, the Huns, the Pathans and Mughals—everyone that has mingled with one another to form one single body of people. It was the turn of the Brahmins now to ‘purify’ themselves, so that they could hold the hands of others. Is India yet ready to listen to Tagore intently? Is any country of the world?

Beyond human concerns, or more appropriately, one of his deeper human concerns, was his passion for the preservation of the nature. Nature was not to be enjoyed or exploited alone, but had to be cherished for human survival. It was he who initiated Vana Mahotsava as a ritual at his Santiniketan school, which has later become a national institution.

Here is a poet, and a human being with profound human concerns. We can stop listening to him only at our own peril.